Exposure to lead, a toxic metal, can lead to serious health issues, including intellectual disabilities, cardiovascular diseases and kidney problems. Children are particularly vulnerable, absorbing lead four to five times more than adults. According to the National Blood Lead Level Survey, three out of four Bhutanese children aged one to six have lead levels exceeding 3.5 micrograms per deciliter in their blood. There is no identified threshold or safe level of lead in blood. The health ministry launched this survey on 25th October, to mark International Lead Poisoning Prevention Week.

According to the health ministry, 3.5 micrograms per deciliter was used as a threshold because it is the detection limit of their device and also aligns with the action levels set by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

Almost 76 per cent of the children between the ages of one and six were found to have blood lead levels above the threshold.

The World Health Organization identifies a blood lead level of five micrograms per deciliter as concerning. In the survey, more than 51 per cent of the children were found to have blood lead levels exceeding this threshold.

The survey tested nearly 3,000 children aged between one and six, along with over 120 pregnant or breastfeeding women and more than 200 children aged below 13 years from monastic institutions.

“When we look at the findings around the world. So, first, the pioneer in the USA, where they had around 2.5 per cent of children aged 1 to 6 with elevated blood lead levels, which is around one in 50 children being affected. And here in Bhutan, it is three in four children with a blood lead level higher than 3.5 microgram per deciliter, which is very concerning for us,” said Kinley Dorjee, a lead researcher at the Ministry of Health.

“Children, the younger they are, they put everything in their mouths. So if there’s lead on something, it’s going to more likely enter their body. And finally, the lead that goes into small children. There is a covering across the brain called the blood-brain barrier. Until about five years of age, it’s more permeable, and it will allow lead to come into the brain, and it permanently deposits there. That is why the risk is so much higher for a small child in the early years of life,” said Dr Phillip Erbele, Asst. Professor/ Pediatrician, Faculty of Nursing and Public Health.

He added that lead exposure in children can lead to developmental delays, learning disabilities, and behavioural issues, among others.

To reduce the risk of lead exposure, he recommended avoiding known sources of lead, taking good nutrition and maintaining hygiene.

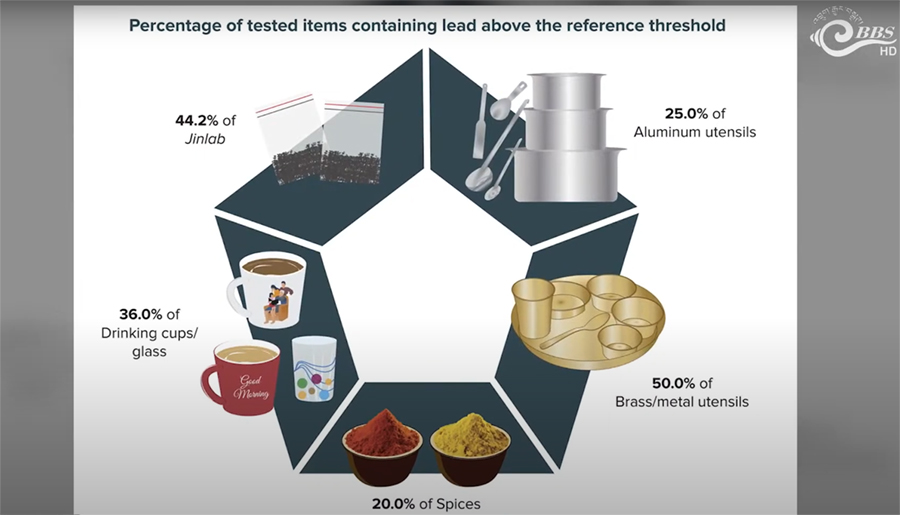

The survey also tested 67 household items such as metal utensils, cups, glasses, spices and Jinlab for lead content. It found that 50 per cent of the brass or metal utensils, a little over 44 per cent of Jinlab, 36 per cent of drinking cups or glasses, and 20 per cent of spices had lead.

The survey also found that over 75 per cent of the religious items tested had lead. Similarly, 86 per cent of the children in monastic institutions tested had blood lead levels exceeding 3.5 microgrammes per decilitre.

Meanwhile, according to the World Bank’s research, lower-middle-income countries like Bhutan lose over nine per cent of their GDP annually due to lead poisoning.

“Lead would have gone into the brain and made learning more difficult. So, over time, they will be less productive because they won’t have achieved the same level of higher education. So, there’s a study by economists from the World Bank that has shown that just the IQ loss will decrease a country’s GDP by over three per cent, and then the cardiovascular increased costs and risk of death from the long-term effects of lead in adults decreases the gross domestic product of a country by another five plus per cent,” added Dr Phillip Erbele.

He added that Bhutan is losing about Nu 21bn every year due to lead poisoning.

To address the issue, the health ministry plans to raise public awareness about lead poisoning.

“To address this, the Ministry of Health, in collaboration with UNICEF and other partners, will initiate strategies to address the challenges presented by chemical poisoning in children and adolescents. The report presented today demonstrates the urgent need for relevant agencies to collaborate on national strategies to reduce lead exposure, particularly for our children and infants,” said Pemba Wangchuk, Health Ministry’s secretary.

The survey was conducted in two months this year by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the Faculty of Nursing and Public Health, UNICEF, the International Partnership for Sustainable Advances in Health and Development, and the World Health Organisation.

Singye Dema

Edited by Sonam Pem